The Archipeligo Within | The Uneven Map of Filipino American Identity Across States

Being Filipino American in California is not the same as being Filipino American in Ohio. Identity shifts with geography - and organizing must too.

This isn’t just a story about where Filipinos live - it’s about who gets seen, who gets funded, and whose version of Filipino America defines us all. Geography is not just a map; it is a power structure

The Distance Between Islands

Filipino America lives in contradiction. We are both everywhere and unseen - our parades filling city streets while thousands of families remain isolated in towns without another Tagalog speaker in sight.

The tension runs deep: between visibility and vulnerability, between the confidence of density and the quiet endurance of distance. One half of Filipino America moves in networks fluent in advocacy; the other half is still learning its own name in places where the word “Filipino” rarely appears in public life.

A rice cooker hums in a Los Angeles apartment, where families spill from Sunday mass and aunties sell halo-halo beside campaign booths. Here, the air itself feels Filipino; politics and pancit share the same space.

Three time zones away in suburban Georgia, Maria and her husband drive an hour to the nearest Filipino store. Their daughter’s classmates think “Filipino” is a kind of food, not a people. She often feels like a cultural ambassador, constantly explaining an identity her surroundings have never learned to recognize.

From California’s density to Georgia’s distance, Filipino America stretches like its homeland—an archipelago of belonging, each island shaped by its own tide.

The Mirage of a Single Identity

Filipino America is often treated as a monolith - one face, one story, one community. But this imagined unity dissolves the moment you zoom in.

We are 4.5 million people scattered across fifty states and thousands of contexts: a nurse in Houston, a teacher in Queens, a coder in Phoenix, a caregiver in Tampa, a student in Iowa.

Every state bends the definition of “Filipino American” to its own landscape. In some, it means legacy and visibility; in others, it means being the only one. Our common flag conceals uncommon conditions.

To pretend we share a single story is to mistake the map for the terrain. Maps flatten. People don’t. Our differences are not liabilities. They are cartographies of resilience. The danger lies in thinking one coastline defines the country.

From Clusters to Constellations

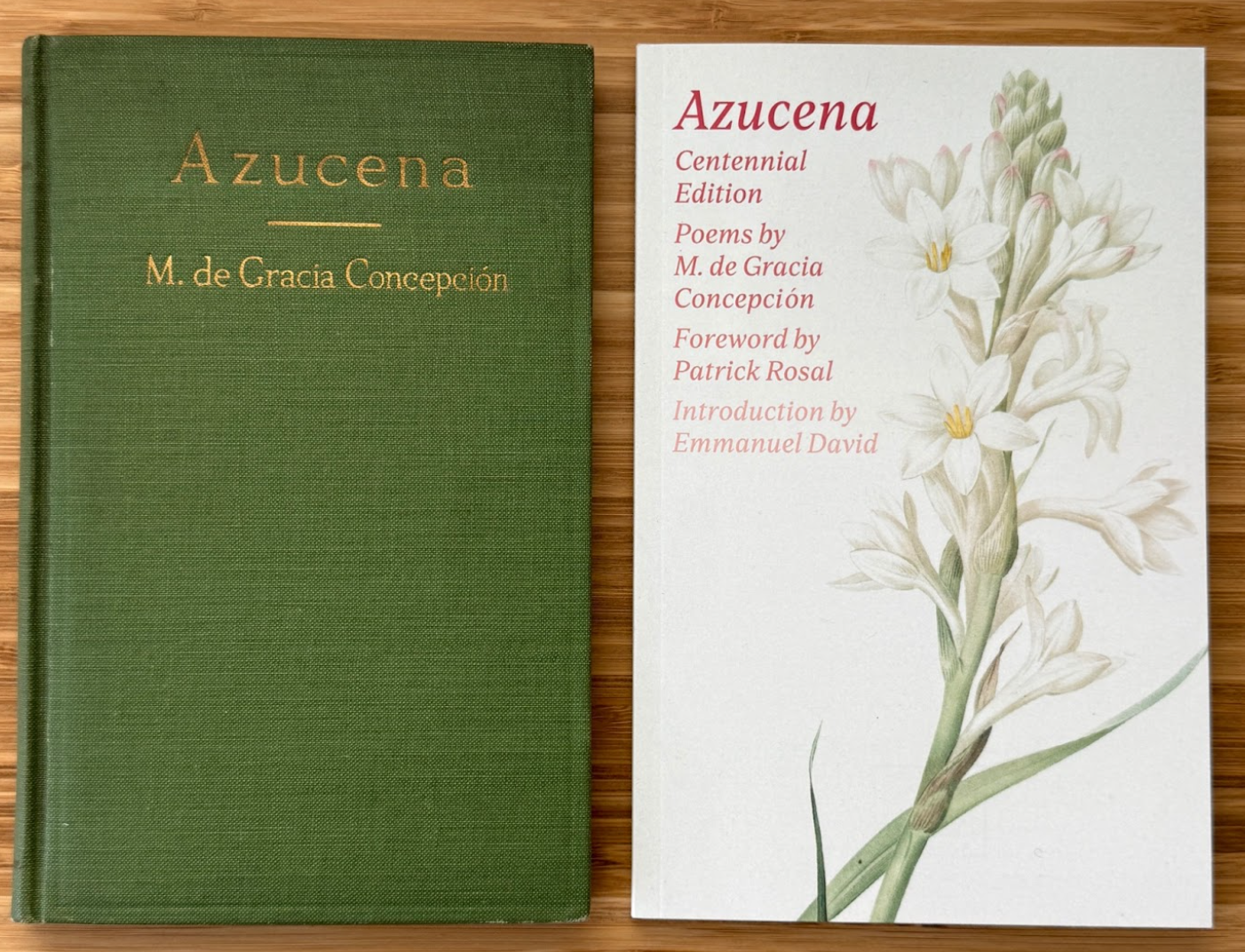

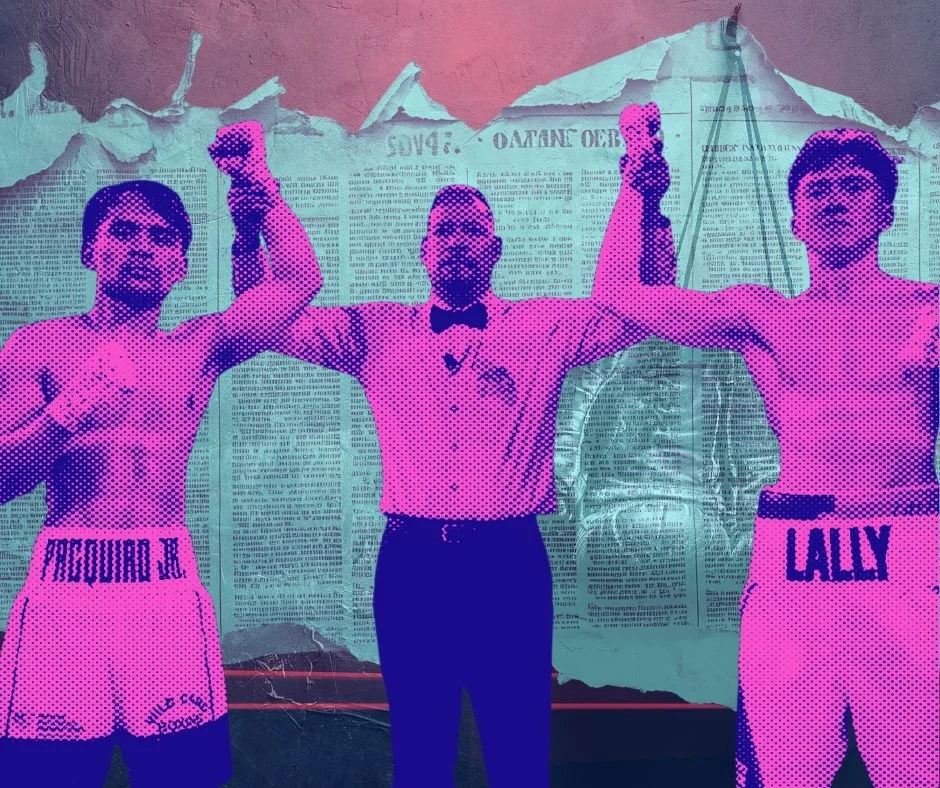

Colonial history taught Filipinos to equate mobility with success; migration scattered that lesson across fifty states. Filipino America grew in phases - each migration wave building a new layer of language, class, and consciousness.

Phase One: Labor and survival (1906–1930s) — farmworkers and pensionados in Hawaii and California.

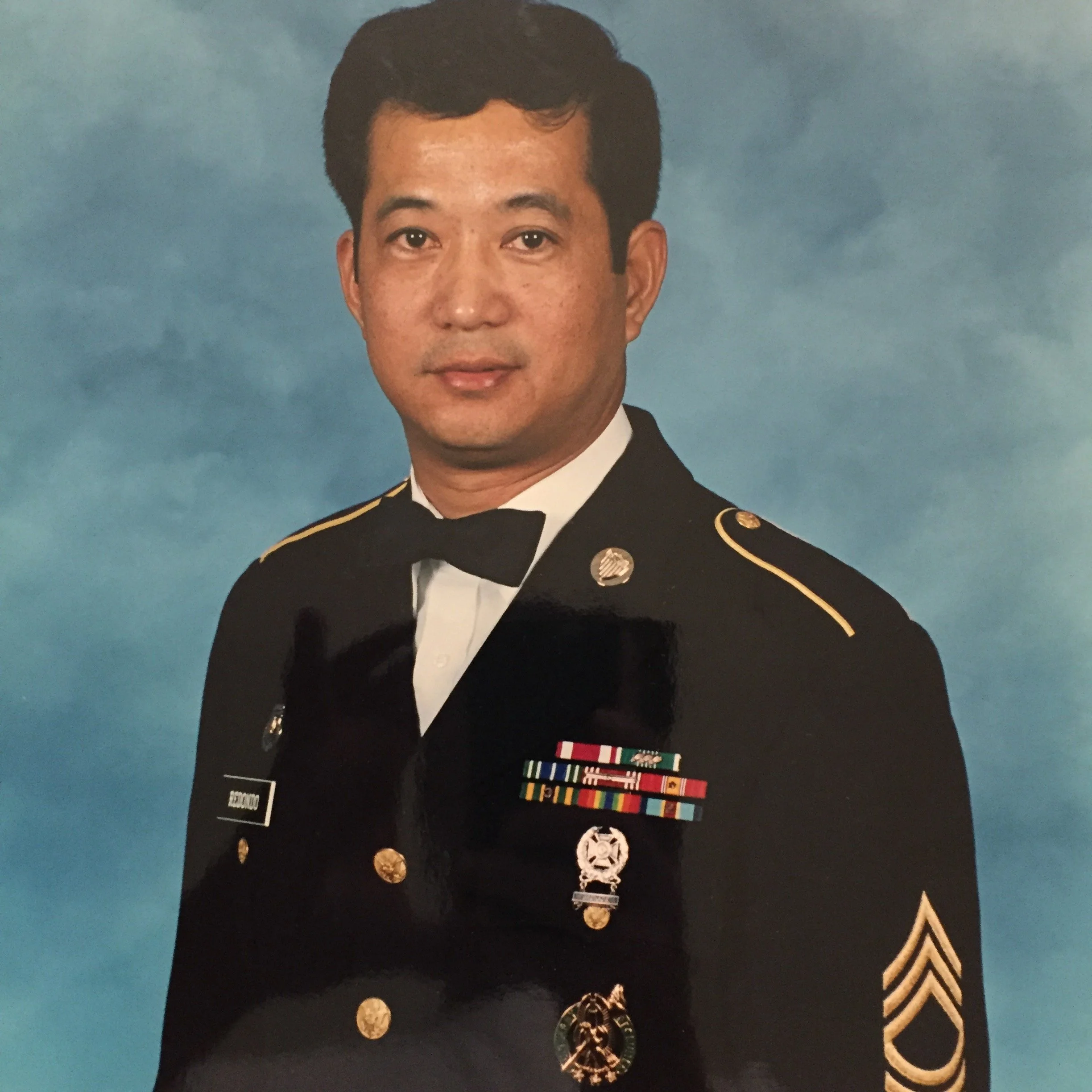

Phase Two: War and reentry (1940s–1960s) — veterans and war brides navigating loyalty and marginalization.

Phase Three: Professional migration (post-1965) — nurses, engineers, and teachers establishing urban enclaves.

Phase Four: Family reunification (1990s) — transforming neighborhoods into self-sustaining communities.

Phase Five: Dispersal (2010s–today) — families migrating inland to the South and Midwest for affordability and opportunity.

This uneven evolution explains why identity feels mature in some places and emergent in others. California and New York speak in the language of legacy. Texas and Georgia, in the dialect of discovery.

A Geography of Belonging

Where Filipinos cluster, infrastructure follows. California and Hawaii together hold over half of all Filipino Americans, where cultural visibility mirrors political influence.

In New York and New Jersey, activism intertwines with artistry, merging policy tables with performance stages. In Texas and Arizona, growth outpaces recognition; community life thrives in fragments. In Georgia and the Carolinas, connection is intimate but fragile, built in church basements, karaoke halls, and group chats that double as support systems.

The same flag waves, but under different skies.

The Privilege of Density

To grow up Filipino in Daly City or Queens is to inherit belonging as default. To grow up Filipino in Wichita or Augusta is to construct belonging from scratch.

Density gives confidence: the luxury of being unafraid to be seen. Distance breeds resilience: the artistry of survival through scarcity.

But privilege carries responsibility. The Filipinos surrounded by abundance - festivals, consulates, elected officials - must not forget those who thrive without it. Representation means redistribution: of knowledge, funding, and visibility.

The Privilege of Density Index:

High: CA, HI, NY, NJ | Medium: TX, IL, NV, WA | Low: GA, AZ, OH, KS, NC, IA.

High-density states inherit confidence. Low-density states invent community. Both deserve investment.

The Politics of Proximity

Proximity breeds both solidarity and conformity. In cities where Filipinos live within walking distance—Los Angeles, Daly City, Jersey City—culture becomes kinetic. People bump into each other at parishes, markets, and campaign launches. Neighborhoods evolve into ecosystems where visibility is not earned but ambient.

That closeness accelerates development: nonprofits find volunteers easily, fundraisers fill overnight, and local officials know that a Filipino endorsement can sway elections.

But proximity also shapes ideology. In dense coastal enclaves, younger Filipinos lean progressive, steeped in coalition politics, immigrant rights campaigns, and racial justice frameworks. Visibility there teaches confidence and civic fluency. In the South and Midwest, where the community is often church-based and insulated, Filipino politics can tilt conservative - guided by family values, faith, and a sense of moral stewardship. A nurse in Houston may vote differently than a student organizer in Queens, not because they disagree on identity, but because their geography dictates what “survival” looks like.

Religion follows the same contours. In Texas, Georgia, and Florida, parishes double as both cultural centers and moral anchors; Sunday attendance is as much community maintenance as devotion. In California and New York, faith coexists with pluralism - mass on Sundays, rallies on Mondays, drag brunches on weekends.

Where proximity to diversity is high, religion softens into inclusion. Where isolation persists, faith becomes the last and only public institution holding people together.

Faith, Food, and the Fragments That Bind

When government support is absent, Filipinos do what they’ve always done: organize through the sacred and the stomach.

In Dallas, Simbang Gabi stretches across twelve nights of worship. In Phoenix, Filipino ministries rent gyms for adobo cook-offs that double as medical drives. In Queens, Jollibee becomes the informal parliament of the diaspora. And in Atlanta, the parish parking lot overflows during Christmas novenas, where volunteers serve hot chocolate beside a voter registration table.

Faith and food form the first public architecture of belonging, offering structure before infrastructure, compassion before bureaucracy. Every potluck is an act of policy. Every mass, a community audit.

A Second-Generation Dilemma

If the first generation built survival, the second is building mirrors.

In Iowa, Filipino youth grow up in cultural isolation. They are archivists without archives, reconstructing heritage through YouTube dances and family recipes.

In Queens, Filipino youth inherit a robust cultural ecosystem. They join leadership conferences, mentorship networks, and protests where “Filipino” is shouted, not whispered.

The difference is not just material. It’s psychological. Where density grants continuity, isolation breeds creativity. Geography dictates not just access to resources but to imagination.

The Politics of Density

Numbers decide who gets heard. In states with critical mass, Filipinos hold offices, unions, and coalitions. In smaller states, visibility is piecemeal and political power is improvised.

Of more than 150 Filipino American elected officials nationwide, seventy percent serve in just three states: California, Hawaii, and New York. Power follows policy, and policy follows population.

In Queens, volunteers run a phone bank switching between Tagalog, Ilocano, and Kapampangan. In Houston, a nurse organizer drives home after a night shift, her trunk full of flyers and pancit trays - activism running on fatigue and love. In Tucson, college students table outside a football game to gather signatures for the first Filipino American History course in the state.

Power and Policy: Who Gets Funded, Who Gets Forgotten

Resources follow visibility, not vulnerability. Less than three percent of Asian-American philanthropy reaches Filipino-led organizations, most of them on the coasts.

The result: a moral geography where power mirrors privilege. Education follows the same pattern - Filipino Studies programs thrive in California but are ghosts in the South and Midwest.

Policy follows population, not potential. And power follows both.

Contradictions in Representation

Filipinos are the second-largest Asian group in America, yet remain marginalized in leadership and philanthropy.

Class divides deepen the distortion: professionals dominate public image, while working-class Filipinos remain invisible even as they sustain community life. Visibility without velocity is pageantry. Representation without redistribution repeats inequality in another accent.

Coastal leaders acknowledge the blind spot: national unity is declared but rarely funded. Meanwhile, in low-density states, pan-Asian coalitions are lifelines, but Filipino equity within them remains an unfinished project.

Faith, Food, and the Fragments That Divide

The same faith and food that bind us can also constrain us. In many towns, the parish is both sanctuary and gatekeeper, offering refuge while policing morality. Conversations on gender, queerness, and mental health often stop at the church door.

“I love my church,” an anonymous member in New York. “But I learned to hide my girlfriend so I could keep singing.”

As one priest from New Jersey confides, “We feed souls, but rarely free them.”

For the diaspora to evolve, it must translate faith into service, ritual into rights, and community into coalition.

Not One America, but Many

What began as geography now becomes memory.

In California, being Filipino means civic confidence. In New York, advocacy. In Texas, enterprise. In Arizona, experimentation. In Georgia, faith turned family.

Each version is real. Each is necessary. Different roads, same compass. Together they form the polyphony of Filipino America - uneven, overlapping, but inseparable.

The Geography of Legitimacy

Legitimacy in Filipino America often equates with visibility. A Filipino in Queens is treated as belonging; one in Kansas, as anomaly.

That hierarchy mirrors the colonial logic of Manila and its provinces. To mature as a diaspora, we must replace hierarchy with federation - belonging defined by participation, not population.

Power is not where people are; it’s where people organize.

The Call Across the Map

The next generation of Filipino leadership may not rise from Los Angeles or New York but from Phoenix, Houston, or Atlanta.

Our power will not be measured by headlines, but by how far hope travels before it fades. Filipino America is not one coastline. It is a continental diaspora - an archipelago stretched across asphalt and time zones.

To build power, we must fund the small islands too: the Midwestern nurses, the Southern youth, the church choirs that double as town halls. Filipino America is not one island. It is a constellation.

Every dot on the map deserves to shine.

The Rice Keeps Warm

Months later, Maria - the woman from Georgia - organizes her first community night in the basement of her parish. Her daughter passes out voter forms beside trays of lumpia. “We’re not the only ones anymore, Mama,” she says softly.

The scent of adobo fills the hall as parishioners talk about the next election. The same rice cooker from her kitchen sits on a folding table, keeping warm through the night.

From California streets to Georgia’s church basements, the rice keeps warm; the recipe changes, but the hunger - for belonging, for power, for home - remains the same.

When the Avengers: Doomsday one-year countdown dropped, audiences didn’t just watch. They paused, replayed, shared, and even speculated about hidden messages. A week later, the clip surpassed 14 million views, becoming a viral moment picked up across major media outlets that fueled anticipation for the next chapter of the Marvel Universe.

The countdown video was the result of a collaborative effort led by AGBO and its studio partners. Supporting the marketing team as a contracted editor was Joshua Ortiz (@joshuajortiz), a Filipino American filmmaker whose career has steadily built toward opportunities to contribute to projects of this scale, alongside earlier success with the short films he has written and directed.