Filipino Rough Riders & The Wild West | Discover A Hidden Chapter in American History

As Filipino-American History Month (FAHM) commences, it's crucial to acknowledge an often-overlooked aspect of Filipino-American heritage: the "Filipino Rough Riders." Professors Emmanuel David and Yumi Janairo Roth have extensively researched this forgotten group, publishing their findings in February 2024 in Playing Filipino: Racial Display, Resistance, and the Filipino Rough Riders in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West .

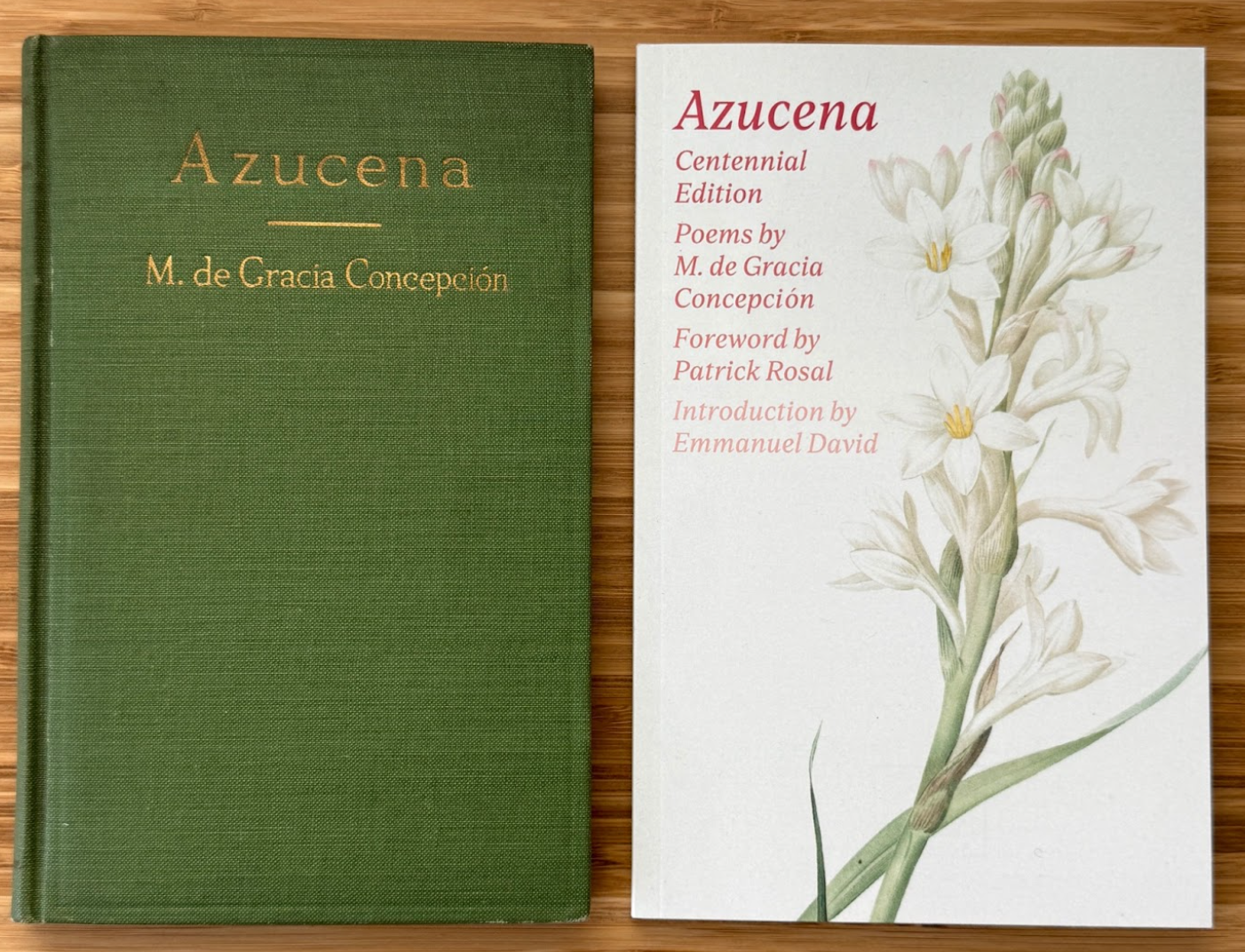

Photos at the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art by Krystal Ramirez. Courtesy of the artists and David B. Smith Gallery

David and Roth's research highlights the significance of Wild West shows, revealing how Filipino performers were among the first to migrate to the U.S. after the Spanish-American War, becoming some of the first colonized subjects to set foot on the American mainland. These shows, popular in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, often dramatized conflicts between Native Americans, white settlers, soldiers, and cowboys, the familiar "cowboys and Indians" narrative. However, the presence of Filipinos in this context is rarely recognized. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, the most famous touring show, ran for forty years and holds a particularly important, yet often omitted, two-year period in Filipino-American history.

By the late nineteenth century, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West expanded to incorporate performers from territories newly acquired by the U.S. as colonial possessions: Cuba, Puerto Rico, Hawaii, and the Philippines. From 1899-1900, three Filipino performers: Geronimo Ynosincio, Felix Alcantara, and Isidora Alcantara were recruited to join the show. Hailing from Manila and other provinces in the Philippines, they traveled to New York to begin the 1899 season at Madison Square Garden. In the subsequent 1900 season, Gregorio Azarraga, Eustaquio Caliz, Ysidoro Constantina, Lorenzo Eman, and Filimon Ermoso joined the original Filipino Rough Riders.

Photos at the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art by Krystal Ramirez. Courtesy of the artists and David B. Smith Gallery

The inclusion of the Filipino troupe aimed to connect Buffalo Bill’s Wild West with the U.S.'s post-Spanish-American War territorial expansion, offering audiences a glimpse into "the population of our coming acquisition." With the end of the Spanish American War, the Filipino troupe served as an educational tool for Americans reading stories about the newly declared Philippine American War. During their 11,111-mile journey across the United States, performing nearly 350 shows over 200 days, the group of Filipino performers faced hostility and derogatory portrayals in the press. Their entry into the arena in traditional Filipino attire was often met with boos, hissing, and sometimes silence.

David and Roth's research has been brought to life through artwork displayed in the Living Here exhibition at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art. The exhibition had a soft opening in June and officially opened on September 5, 2025, and will remain on display until December of this year.

1. Tell us about yourselves.

Emmanuel David: I am Emmanuel David. I'm Filipino-American and I've lived in Colorado for most of my life. I was born and raised in Denver. I have an interest in Philippine culture, history, and the diasporic experience. I went to Loyola in New Orleans for undergrad. My PhD work was at University of Colorado.

I'm faculty in women and gender studies at the University of Colorado, and I teach gender studies and queer theory courses.

I'm trained as a sociologist and as an ethnographer. I go out into the world and try to understand how people find meaning in the things that they do. A lot of my projects are trying to figure out how people make sense of their lives, the people around them, and the activities that they engage in.

Over time, my intellectual curiosity became more focused on studying the Philippines. For the last 15 years, it has been almost solely about Philippine culture, and now the Philippine diaspora in the United States. The work I’m doing now toggles between life in the Philippines and life of Filipinos here in the States.

Yumi Roth: I'm Yumi Janairo Roth. I grew up in Chicago, then moved to the east coast, outside of Washington D.C I lived in the Philippines as a little kid, during the period that martial law was declared. I went to Tufts in Boston for undergrad, then went to SUNY for an MFA. Later, I ended up in Colorado.

Even though I’m not from Colorado originally, I've lived here a long time. My grandparents on my father's side retired here, so I've known this part of the country for a really long time. I moved out here in the early 2000s when I got a job teaching at the University of Colorado Boulder where Emmanuel and I both know each other.

I’m an artist and a professor of sculpture and post studio practice at CU where I've been teaching for 20 plus years. With “sculpture” you often think of objects, but “post studio” extends the practice outside and into the world. This is where our interests intersect.

2. Tell us about the work that you're currently doing.

Emmanuel David: We have an exhibit up at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) at the Barrick Museum of Art. It’s part of a group show on Asian and Asian-American diasporic experiences. It's not just Filipino, but it's the diasporic experiences of East and Southeast Asians.

Yumi Roth: We started working together around the time when people were emerging from COVID, spring of 2021. Over lunch we started talking about Filipinos in the Rocky Mountain West. Being Filipino in this part of the country, we are either misunderstood or invisible. Most people in this region don’t really know much about Filipino culture. It made us think about Filipinos in the present day American West as well as historically. We ended up on this meandering trail about the turn of the century when Filipinos were appearing in various exhibitions like the World’s Fair in St. Louis.

Emmanuel David: We were trying to research and find stuff but there was almost nothing available. We did find some mentions of Filipinos in material digitized at the Denver Public Library. The library holds the papers of Nate Salsbury, the business partner of Buffalo Bill. He meticulously collected information and made scrapbooks from newspaper clippings from all the different places the Wild West tour traveled. It was from these scrapbooks that we first came across the Filipino Rough Riders.

3. Before we continue on, can you give our readers background of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows?

Yumi Roth: In the 1800s, the U.S. government tried to settle all the land west of the Mississippi, all the way to California down through what was once part of Mexico. Wars were still happening between Native Americans and the US government, they were trying to put people on reservations, there were broken treaties. This is the overarching story of a settled American West.

By the late 1800s, Wild West shows started to appear, reconstructing a national heritage or a belief in a national mythology. Buffalo Bill, Westward expansion, cowboys and Indians – that’s the known narrative. Buffalo Bill was the most successful version of that. He was one of the first and he by far the most successful of the wild west shows. Millions of people around the country were able to see the show.

Buffalo Bill met presidents, royalty, and the most important civic and business leaders almost wherever he traveled. The show was one of the biggest entertainment platforms that set the stage for the ways in which we inherit ideas about the American West in contemporary times like in films about cowboys and Indians. This narrative was reenacted during the Wild West show. There's a massive reverberation that happens as a result of the Wild West show.

Emmanuel David: It was a constructed narrative that was intentionally devised to send certain messages about who is civilized and who is not civilized. A lot of this was portrayed to audiences not in the West ––not in California, not in the Rocky Mountain West, not in Texas –– but mostly for those in the Midwest and the East Coast. The key locations for these displays of this narrative were in places like New York, Philadelphia, Washington D.C., Chicago and the Midwest. It was a performance of the west, mostly for people not in the west, to tap into this imaginary western frontier.

The show constructed a story about good guys and bad guys. The good guys were always the white guys who triumphed over Native Americans in an ongoing struggle over land, resources, and morality. That portrayal continued for many decades. What eventually happened was that the western frontier jumped the Pacific with the Spanish-American War and the U.S. presence in places like the Philippines, Cuba and Puerto Rico. This Western expansion was no longer bound by the continental US. It was part of the expansionist thought and it was in this moment where the United States became a colonial power as well. In 1898, during the Spanish-American War, the U.S. acquired the Philippines for $20 million – then all of the sudden the Philippines became a U.S. colony. This “real life” event is what got folded into the narratives that were being performed in these Wild West shows.

While this is a highly political historical moment, it also got folded into the popular culture of the time. There was no televised news at that time. One of the ways in which historical episodes got circulated was either through newspapers but also through popular culture. This became one venue through which the stories of American conquest like American colonial projects got played out for audiences in the U.S. We had to reconstruct this story. We had to put together these pieces of the puzzle: How did three Filipinos get here in 1899, then five more in 1900, and end up in this show? And why?

Those who were producing the show sought out representatives of “our” new colonies. We use quotation marks around “our,” because the show referred to the Philippines as “our strange new possessions” – because the Philippines was imagined as some strange place way over there. People were hungry to understand what our so-called “little brown brothers” would look like. They wanted physical evidence and to be able to see them in the flesh. And so the show’s talent agent recruited two men and one woman to start performing in 1899.

Yumi Roth: At the same time, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West also brought in a group of Hawaiians. There was a group of Cubans who came to reenact the fall of the Spanish in the Spanish-American War. In 1899, the Philippines was one of the United States’ new far-flung possessions but by the time the show was able to get the group of Filipinos over to the U.S., within just months, the Philippines was at war with the United States. Of course, the Philippines was not happy to be turned over as one colonial possession to yet another colonial power.

At this moment, Filipinos were brought over to perform as new subjects of this great colonial empire. They were performing under these rapidly shifting conditions in the U.S. These three individuals were representing something larger than themselves.

Emmanuel David: In U.S. history, the Philippine American War is something that doesn’t really get brought up or taught – that’s by design! It’s not a feel-good memory that most Americans want to embrace or remember. We're trying to reconstruct the histories that have been omitted.

Americans were committing these atrocities and acting as an imperial power against a group of people that wanted liberation, freedom, independence. The Philippine American War is often talked about as the Philippine Insurgency. And the group of Filipino performers, at times, became equated with an enemy. That explains why they were met with hostility –– boos and hisses –– in places like Madison Square Garden.

Yumi Roth: As we've delved into it, we realized and understood the importance of that historical moment and then the erasure of that historical moment, we've come to understand it as more pivotal rather than a footnote to history.

Imagine the United States engaged in some war, and then at the same time seeing people of that country that they’re at war with, being represented in other ways, side-by-side. The Filipino Rough Riders were caught in the middle of all this. It creates a lot of dissonance, but it also tells you something that it wasn't a footnote in history. It was actually a cultural moment and a political moment for the U.S. and the Philippines.

Photos at the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art by Krystal Ramirez. Courtesy of the artists and David B. Smith Gallery

4. Tell us about your art exhibit at UNLV.

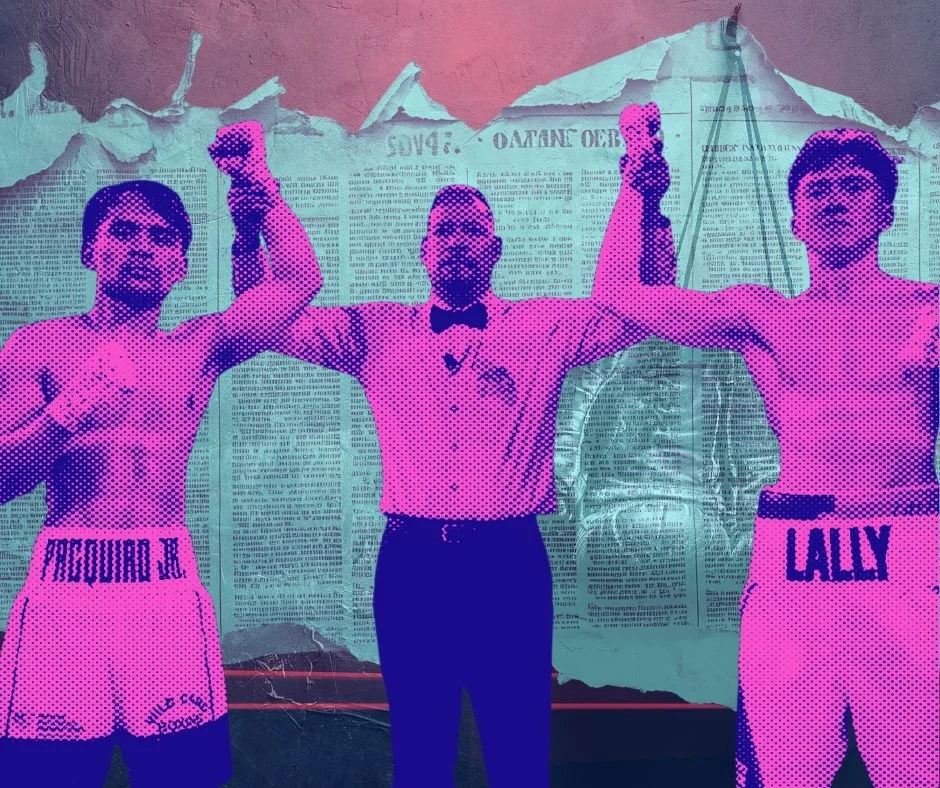

Emmanuel David: In 1899-1900, no other racial group in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West got as much press as the Filipinos. We came across a group photo where we saw these Filipinos on the edges, as if they were only part of the supporting cast. In our project, we tried to imagine what their lives looked like, so we found a medium for the gaps in history that allowed us to imagine other possibilities.

Yumi Roth: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West traveled over 11,000 miles in a season. We imagined what their journey would have been like, and all the cities where they stopped by. Related to the work in Living Here, we went to old theaters where we put the names of the Filipino “stars” of the show up on the marquee for an on-going, travelling project called We Are Coming.

Emmanuel David: Recently, we visited some of the red states and activated We Are Coming in those places, during some of the anti-immigration moments taking place in the present day. Our messaging had been centered around “we are coming” but now, it also became important to say “we are already here.” We were no longer thinking just about future waves of immigration. We also wanted to shift attention to immigrants that are already here. In this way, this project isn't just about historical politics – it's about politics in the now and it's a commentary on the continuities and discontinuities like anti-immigration.

Yumi Roth: The Buffalo Bill Museum had a route book, which was a souvenir object. We used that route book of their schedule and stops to create some of the art in Living Here. We worked with local jeepney sign painters from the Philippines to create the work.

Emmanuel David: We created art work that put the Filipinos front and center, as if they were the stars. We mixed in the locations and dates of the 1899 performances, and peppered in some Filipino phrases and contemporary slang, like astig (awesome) and lodi (idol spelled in reverse). We worked with four different artisans, all have their own style of hand painting jeepney signs. This is almost becoming a lost art and skill.

Yumi Roth: We also have some photographs of Filipino cowboys and cowgirls from an annual rodeo in Masbate that we attended. We took some portraits of modern day cowboys and cowgirls that we met during our time in the Philippines.

Photos at the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art by Krystal Ramirez. Courtesy of the artists and David B. Smith Gallery

5. What are you hoping folks will get out of visiting your exhibit?

Emmanuel David: That this is largely an untold story about Filipino history, one that enriches our understanding of the diasporic experience. This is a group of three to eight people, and they each had a story. It's kind of a charge to have us think about all of the stories that people in our community, our elders, and our parents – they all have their own stories.

Yumi Roth: I want them to come away with whatever they're going to come away with. We put out the various art pieces that we have found compelling or interesting to ourselves, but we can't drive the interpretation. The most interesting encounters that I have with people are when they experience some kind of discomfort or friction – that’s a good thing because it’s a way for us to revive this forgotten history. People will now start to think about why this has been sidelined. Some may feel some discomfort because what they thought they knew, what their assumptions were and what they’re being confronted with, is seen in these works.

6. Where can people see the exhibit and until when?

Our work is part of the Living Here exhibition at UNLV’s Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art. It will be up until December 20, 2025. The museum is open from Tuesday - Saturday, 10 AM - 5 PM. It’s free and open to the public.

7. Where can people find you?

You can find more about our work at:

Instagram:

@e_mmanueldavid

We Are Coming: https://spot.colorado.edu/~rothy/weAreComing.html

Last Year’s Wonder’s All Surpassed: https://www.davidbsmithgallery.com/exhibitions/101-last-year-s-wonders-all-surpassed-yumi-janairo-roth-and-emmanuel-david/

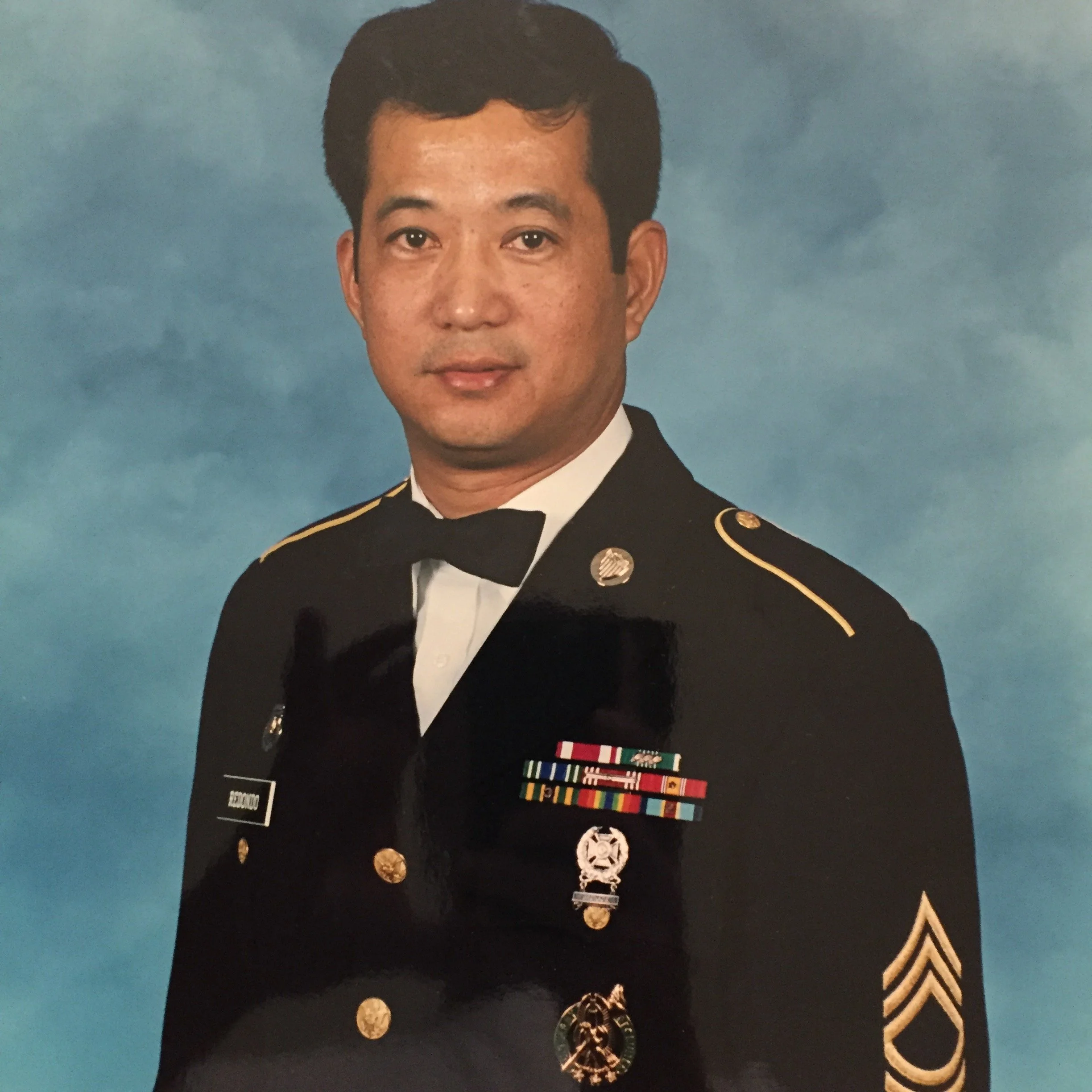

Written by Jennifer Redondo

Co-Founder and Co-Author of In Her Purpose

When the Avengers: Doomsday one-year countdown dropped, audiences didn’t just watch. They paused, replayed, shared, and even speculated about hidden messages. A week later, the clip surpassed 14 million views, becoming a viral moment picked up across major media outlets that fueled anticipation for the next chapter of the Marvel Universe.

The countdown video was the result of a collaborative effort led by AGBO and its studio partners. Supporting the marketing team as a contracted editor was Joshua Ortiz (@joshuajortiz), a Filipino American filmmaker whose career has steadily built toward opportunities to contribute to projects of this scale, alongside earlier success with the short films he has written and directed.