Two Peas in a Pod: FilAm Twins Rosalyn and Carolyn of Netflix’s You Are What You Eat

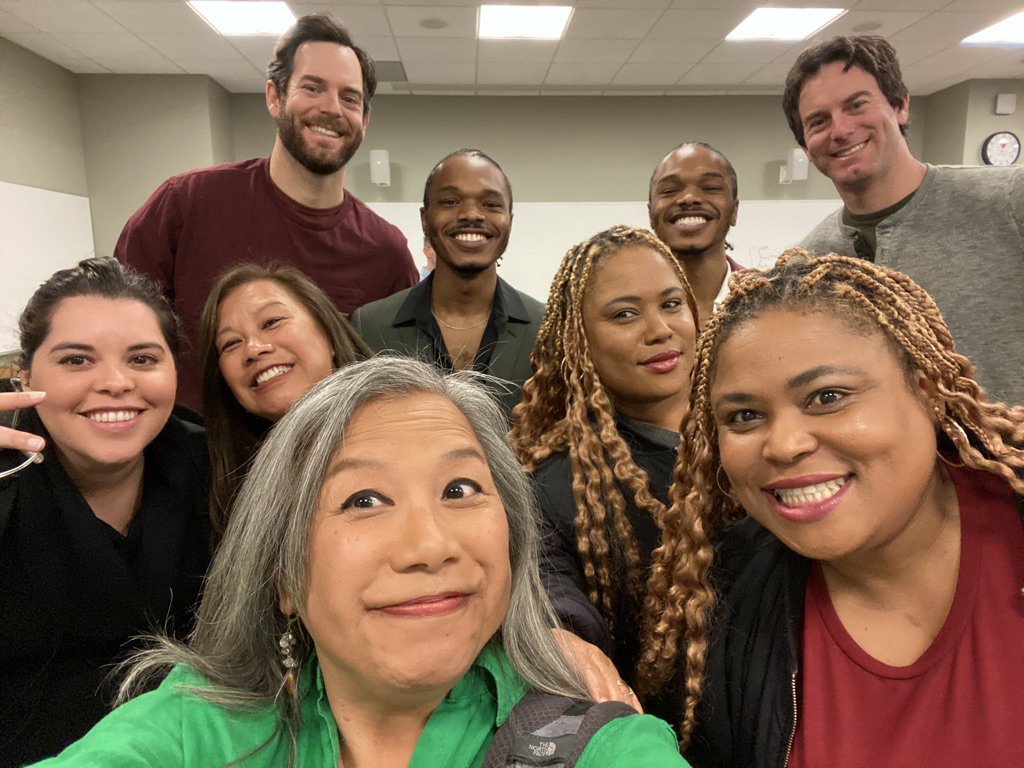

Filipino American twins, Carolyn and Rosalyn, participated in Netflix's You Are What You Eat project, aiming to enhance the presence of Filipino individuals in scientific research. Carolyn, a sports relationship coach, and Rosalyn, a teacher, took part in the experiment where Carolyn adopted a vegan diet while Rosalyn continued with an omnivorous diet. Explore their experiences and discoveries regarding diet, genetics, health, and life throughout the experiment. We got the opportunity to sit down with Carolyn Sideco and Rosalyn Moorhouse. Here’s the scoop!

1. Who are the Filipino twins on Netflix’s You Are What You Eat?

Carolyn Sideco: I'm Carolyn Sideco. My pronouns are she, her and siya. I am a sports sports consultant. I do spiritual, life and relationship coaching. I'm much more well known for being a monozygote, with Ros, my sister. We were born in the Philippines and immigrated here to the United States when we were two years old. We grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area. I currently still live in San Francisco and I now split my time between San Francisco and New Orleans.

Rosalyn Moorhouse: My name is Rosalynn Sideco Moorhouse. You can call me Ros. My pronouns are she, her and siya. Currently, I am a high school teacher at a Catholic school in the Bay Area. I teach in the religious studies department, and I've been there for 23 years. The school in the documentary you see me teaching, that's my class.

My Catholic faith is really important to me. After college, I worked at a Christian agency that ran group homes then I became a youth ministry coordinator at a parish in Cupertino. I have my Masters Degree in Pastoral Ministry with an emphasis in Catechetics (Religious Education).

2. How/why did you decide to join the twins experiment on Netflix?

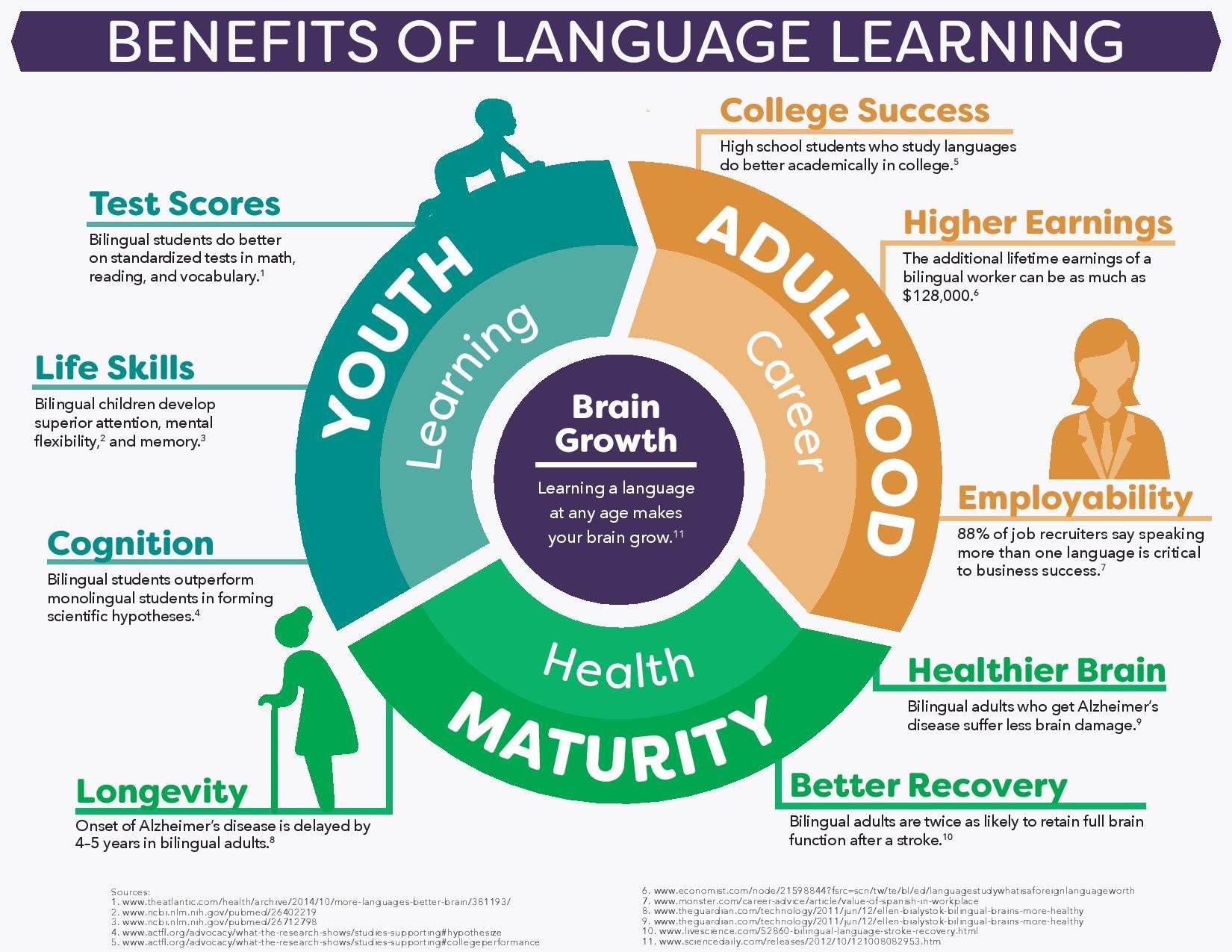

Carolyn Sideco: For a couple of decades now, we've been involved as participants in Stanford’s National Twin Registry. This registry consists of twins who are called upon to do scientific research. We’ve done several twin studies before coming on the show. One of my favorite studies was the facial recognition software that we were testing right after 9/11. We were recruited to see if we could fake out the software. We've been involved with medical research related to allergies, vaccinations, language studies, and so many more.

Researchers are interested in twins because of the controlling genetic factor. Being identical twins, we have the privilege to take part in these kinds of studies. For the Netflix documentary, 22 pairs of twins were part of the study. Though only five pairs were men, and the rest were women. However, only two to three sets of twins were women of color. The majority of the participants were predominantly white women.

Based on general statistics, there is an underrepresentation of Asians and Filipinos, specifically in scientific research. We want to encourage even more participation not just from Filipinos who are twins, but from Filipinos in general.

3. What was the biggest challenge, while adopting a new diet and exercise regimen?

Rosalyn Moorhouse: It's clear that vegans encountered most of the challenges! For me as the omnivore, the fitness component was more of a challenge. It was an opportunity to get back into shape and be more mindful of my eating patterns. Food and eating were not very challenging because nothing was really off the table, except Stanford nutrition made it a point for both of us to eat healthy.

Carolyn Sideco: Ros, you were saying that the fitness part is what got you hooked.

Rosalyn Moorhouse: Yeah, that was probably the only thing that hooked me in. The fitness component definitely got me on board. I needed to get off my butt and get back into shape.

Carolyn Sideco: All of the twins featured on the Netflix series were the only ones who were afforded the fitness training program. We had to submit blood and stool samples. We had to go in for clinical checks. We had to takepart in the fitness component, which included the baseline and post-testing. They also added the body scans and sexual medicine component.

The biggest challenge for me was grocery shopping. I am not a very good shopper. I'm kind of inept in the kitchen. My husband does all of the grocery shopping and food preparation. He was unwilling to take part in any vegan preparation so I had to do it all myself. I was fine for the first four weeks because the food was provided. But then, the last four weeks I had to fend for myself. It was hard to feed myself in the context of my family. Another challenge for me was filming myself while eating, and also making sure that I was eating enough protein. I felt like I was eating all day. I was so tired of eating!

4. In moments of self-doubt, what do you do to build yourself back up?

Rosalyn Moorhouse: I pray. I go back to finding a sense of grounding and perspective. I have various outlets. I have my go to friends who are also prayerful and supportive.

Carolyn Sideco: I rely on the Filipino community. I work with SOMA Pilipinas, and I am on the board of the Filipino-American Development Foundation. I am also one of the Co-Founders of the Bayou Barkada in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Our communities want to do right by one another. That's where I know that I'm not alone. They're with me. I've learned how to rely on the community and kapwa. Not only are we partying together, but we're not going to abandon one another. Right, because we can't afford to.

5. Knowing what you know now, what would you do differently? If anything? (Either or both professionally or personally)

Rosalyn Moorhouse: After the study was done, we learned that the youngest pair in the documentary switched diets. I thought that it would have been kind of fun to do if Carolyn and I had switched as well, just to see what could have been.

Carolyn Sideco: I would have had a plan for the documentary release. The coach and playbook person in me wishes that I planned a little earlier for promotion so that I could have incorporated advocacy. I would have taken more courses in social media to help me create content.

If I have any regrets, it's that we weren’t represented by agents. I wish there was a way that I could have had more support in preparing for this that wouldn't have to cost me any money. It’s already costing us because we weren’t paid for the entire year to be part of the study or documentary. I had to be more flexible and switch out some clients to accommodate the filming schedule. I think about those sorts of structures when it comes to inequity or when it comes to labor or worker rights, especially as this was during the time of the writers strike in Hollywood. When it comes to equity, obviously people of color are being asked to represent. I take that seriously and at the same time, it comes at a cost.

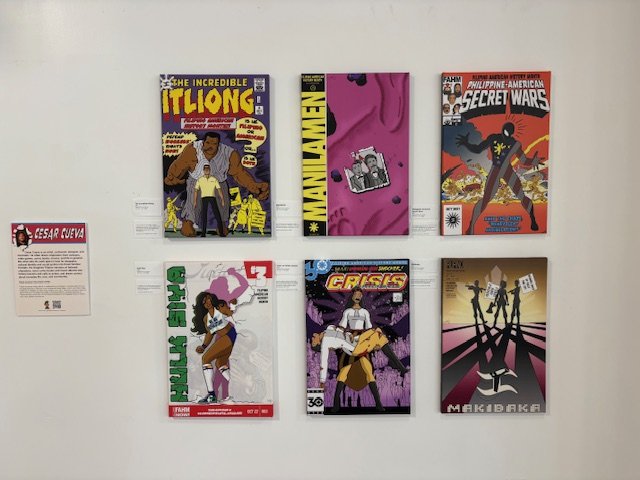

While filming, we were not able to wear branded clothing so I did some product placements for the Filipino community. I wore a couple shirts to shout out the Sama Sama Cooperative which our family belongs to. A number of people asked about the “Donut let your goal slip away” shirt, which is from my oldest son’s fitness company. We have more of those available here for folks to order.

6. Has this experience changed your life? If so, how?

Carolyn Sideco: It's leveled up and amplified my advocacies. I've been able to bring people like Chef Reina into it to get her more shine. The documentary is showing in over 100 countries, and I want to leverage it. Not just within the Filipino community, but also as a token for the Filipino community to rally to join research studies that benefit our communities with health disparities. It is changing my life because it's helping me to connect even more. I want to show my solidarity in the Filipino community. We have this responsibility to our communities and I take that seriously but in a fun way, so if it's through Netflix then by all means.

Rosalyn Moorhouse: I agree with Carol. Now that this docu series is out there in the world, we're probably going to see the tip of the iceberg in terms of changes. Hopefully it will bring a heightened awareness for people to look at these issues that the docu series brings forth. I hope to see those changes take place. There are opportunities that are going to come because of this experience, and for those I’m grateful.

In terms of my life. No concrete changes. I'm still working as a teacher. My primary responsibilities are not going to change. But in terms of changing, on a social level. I hope there is some change so that we can talk about some hard questions related to how we source food, who has access to it, and even some of the deeper reasons for why people are so attached to food. I hope it adds to the conversations that are already going on.

Jennifer Redondo: You know what changed me after having watched the docu series? Seeing you two cook chicken! Prior to watching the show, I already had a problem touching raw meat and cooking it myself. After watching the docu series, it confirmed exactly why I don’t like to touch or cook meat.

Carolyn Sideco: Jennifer, my gosh, maybe we should offer some comfort to you because we were set up. We were unfamiliar because it wasn't either of our kitchens. We couldn't even turn on the faucet. There was no dish soap in the sink. So that's why all that glow germ was everywhere!

Rosalyn Moorhouse: We were opening everything because we didn't know where anything was. It was a scare tactic!

Carolyn Sideco: It's provocative and added some drama.

7. We know that not everyone has the same access to food, and not all countries and governments are equal. What are your thoughts on how our environment dictates what we eat and how we live?

Rosalyn Moorhouse: The docu series featured an example of how some agricultural policies allow businesses to set up shop near residents’ homes, knowing that there is a high chance that their properties will get contaminated. How do we let that happen?

Jennifer Redondo: Here in the United States we have a much lower standard when it comes to food and drug guidelines. When you travel to other countries, take notice of their food labels. I went to the UK for work, and when I looked at the ingredients labels of ketchup and gummy candies, their list was very short. Whereas, here in the U.S., we have a long list of ingredients we can’t even pronounce, additives, preservatives, and things that don’t belong in our bodies.

Carolyn Sideco: Another aspect that I'd like to see lifted up is the global majority. People of color who have urban gardens, who have localized agriculture, who have co-ops of foods that is native to their diet. Food sovereignty – we see that in the Bay Area. The docu series didn't focus on that except in Detroit, but it is a movement that exists!

We have to be critical of large agribusiness because it does touch the broader community more. We can be critical of that and also look to indigenous practices and farming practices of people of color that are sustaining themselves and their communities, thriving off the lands that they've cared for. That's hard to do. I am also admittedly that person who can barely keep a plant alive.

8. For the most part, our ancestors ate farm to table. It wasn’t until Americans came to the Philippines that we got introduced to canned foods. So obsessions with SPAM and Vienna Sausage surfaced. Many doctors say that diabetes and heart disease are genetic. Do you agree or do you think it’s because we are continuing to eat like our parents and because we live more sedentary lifestyles?

Carolyn Sideco: Yeah, I think there's some definite correlations to that. I think especially with the U.S.'s political mandate of benevolent assimilation, and the American form of education imposed on the islands. We couldn't help that. It's not our ancestors fault. They thought this was going to be better. We incorporate that and then this insidious thing about colonization is that we’re told that is our culture. We're told that we're not Filipino if we don't eat pork. Now, millennials that are second, third, or fourth generation Fil-Am are going back to pre-colonial practices because they know the health disparities. They work in these fields and they're tracing that history back. They’re asking if we can replicate a pre-colonial diet. I think what's exciting is that people are trying to answer that in their own ways.

It doesn't hurt to reinvent and reevaluate. I don't want to be that Filipino person who's now in my mid 50s saying, “I'm always gonna eat SPAM because that's what I grew up on because the Americans brought it and I love it.” Filipinos love SPAM, but maybe we can start with the less sodium version? There's a way that we can coexist, for the betterment of everyone. There is that push and pull, but if we are to set in our ways, then we don't allow for the possibility of improving our collective health for future generations.

9. What advice do you have for folks who are looking to make some drastic lifestyle changes?

Carolyn Sideco: Don't do it.

Rosalyn Moorhouse: I agree. Especially if it's drastic.

Carolyn Sideco: A lot of people will not make any changes unless they are drastic. I think about many people who have been disconnected from their own health or well-being and maybe who are unsupported. There are some people who can't afford to get sick because they can't afford to not go to work or those who are parents or caregivers who have to put their own needs aside for other people.

Find people who will help you. Make those drastic changes with those who also need to make drastic changes themselves. Get people around you who will support you. Accountability! Even though we say it's for our own health, we won't do it. Unless it's for someone else. If you need to make changes, you're almost there because if you've already identified that you need to make drastic changes, that's half the battle.

Rosalyn Moorhouse: Christopher Gardner, the lead researcher at Stanford, said that whatever way people can get hooked into making changes for their health, he's all for it. Maybe it's a very personal reason, maybe it's what you see, or your environment. Maybe it's how you saw where food is sourced? Whatever avenue can hook people towards making changes towards a more healthy lifestyle, he’s all for it. It's difficult! There are people like me who fluctuate. We have times of great motivation, and then we have times when we don't. There is value in the attempts to make these things happen towards healthier living.

Carolyn Sideco: The key word is living.

Rosalyn Moorhouse: I think because of my faith I look at is it's not just living here. It's what's really life-giving. And yes, all of us will die. So with that kind of perspective, it should impact how we live.

10. What parts of the study and documentary experience do you incorporate into your current lifestyle?

Carolyn Sideco: Before the study I didn't eat red meat. I haven't eaten red meat in 30 years. If it flies or swims, I'll consider it. In a household where my husband and my son do eat meat, I eat chicken and fish. So for me, it's more adding more vegetables and learning different ways to prepare vegetables and high protein foods like hummus and kimchi. The teachings from our nutritionists were really helpful.

Rosalyn Moorhouse: I did eat a lot of red meat before the study. Now, I will be more plant forward. There's a diminishing of red meat consumption. I can't remember the last time I had red meat. It's those small changes. I don't necessarily believe in restricting myself too much.

Carolyn Sideco: It backfires for me if I restrict myself.

Rosalyn Moorhouse: Me too. So, I am going to have my ice cream. Maybe I won't have a full scoop of ice cream. Maybe I'll have a smaller portion and maybe I won't have ice cream as often.

11. What does it mean to be Filipino?

Carolyn Sideco: This is easy because my purpose is to be Filipino 24/7. If I could do anything I wanted all day long and not have to worry about money, then I would just want to be Filipino 24/7.

Rosalyn Moorhouse: For me, it means an acknowledgment of my roots, to pay homage to my roots but also to do the hard work of reconciling what it means to be Filipino. Maybe not everything about being Filipino is all that great, as there may be some practices that we need to reconcile. We must at least acknowledge that there are some good and not so good. Certainly, we should not ever deny it.

Above all, my faith life is the larger umbrella. Everything else about who I am is subsumed into that. If I were to be asked ultimately, how do I identify? I would say my identity is a child of God who aims to live like Jesus.

12. What else do you want to share with our community and readers?

Carolyn Sideco: We have the resources to support making improvements to our health. I want our readers to know that they are supported in the community. If they want to make these changes, they can.

Rosalyn Moorhouse: Filipinos don’t necessarily have to be tied to the old narratives about who we are and what our contribution is to our community. It's not just about our food, but there’s a richness to who we are. To get to know us, you have to look beyond our food.

13. Where can people find you?

Carol can be found on the following platforms: Instagram @coachingkapwa, LinkedIn, and LinkTree.

Filipino nonprofits are fueling change but funders still treat them like an afterthought. But here’s the brutal truth: They’re doing it on shoestring budgets, unpaid labor, and unsustainable hope.

Read More